"We were one of the last smooth jazz stations to bail on the format. But it's been in trouble for a while. There’s been a shift in the industry, where the quantity of listeners became more important than the quality of listeners. The radio stations that have lots of listeners, regardless of how long they listen, will be rewarded, and the stations whose listeners listen passionately aren’t rewarded. The 'JZA listeners weren’t button-pushers."Read the whole thing here, via Marginal Revolution.

29 December 2010

The Death of Smooth Jazz

Billy Taylor

I don't have much to say about Billy Taylor, who died yesterday. But his importance in the development of jazz studies as an academic discipline cannot be understated. His writing on the subject and work in promoting jazz as art to be taken seriously was crucial to the transformation of the perception of jazz (beginning after World War II with important antecedents from the swing era) from popular dance music to an art form. However, Taylor did not fully subscribe to that dichotomy, often finding a point in his music and writing between art and entertainment that disappointed few.

Below, Taylor discusses cool jazz in the 1950s miniseries The Subject Is Jazz:

Below, Taylor discusses cool jazz in the 1950s miniseries The Subject Is Jazz:

23 December 2010

2010 In Review

Tomorrow I'm off to Miami for the holiday, so I will leave you with my year-end roundup. As the usual disclaimer goes, since I am but an amateur critic, I only review a handful of albums released in a given year, so be sure to check out the best-of lists of the more than capable critics after the break. But before that, here are the albums which I enjoyed the most in 2010, in alphabetical order by artist:

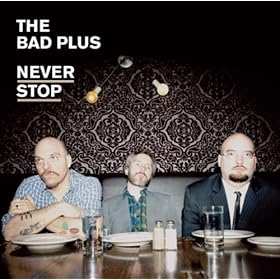

- The Bad Plus: Never Stop

- Vijay Iyer: Solo

- Jason Moran: TEN

- Paul Motian: Lost in a Dream

- Polar Bear: Peepers

- Christian Scott: Yesterday You Said Tomorrow

- The Wee Trio: Capitol Diner Vol. 2

- Beach House: Teen Dream

- The Black Keys: Brothers

- Broken Social Scene: Forgiveness Rock Record

- Spoon: Transference

- Vampire Weekend: Contra

- The Walkmen: Lisbon

- Kanye West: My Beautiful Dark Twisted Fantasy

- The Whigs: In The Dark

21 December 2010

Winter

- Avishai Cohen - Art Deco

- Jason Moran & Stefon Harris - Beatrice

- Medeski Martin & Wood - Partido Alto

- Paul Motian, Bill Frisell & Joe Lovano - Dance

- Charles Mingus - Orange Was the Color of Her Dress, Then Silk Blues

- Chris Potter - Okinawa

- Miles Davis - Freedom Jazz Dance

- Vijay Iyer - Fleurette Africaine

- Miroslav Vitous - Carry On, No. 1

13 December 2010

09 December 2010

James Moody

The only unfortunate part about writing a jazz blog is the fact that it often entails eulogizing, and tonight calls for it. James Moody, the saxophonist whose playing graced the records of Dizzy Gillespie and Kenny Barron, to say nothing of his own recordings, passed away today, succumbing to the pancreatic cancer which had overtaken his body. Lee Mergner posted Moody's obituary at JazzTimes this evening.

The jazz world has lost yet another link to the so-called glory days, but that sentiment sells Moody short as a musician and a man. In 2002 I came home to Miami from the University of Florida one weekend in October to see Moody play a guest concert with the University of Miami Concert Jazz Band. He killed it that night. Playing with the energy of a man less than half his age, his beaming wit was clearly evident in his playing. My memory of the night is hazy, but I do remember being blown away by a rendition of Body and Soul, played with the Miami faculty ensemble to open the evening. I left Gusman Hall in Coral Gables floored by his performance; as a septuagenarian he played with fire, precision, and levity which most of us couldn't dream of pulling off. Even in the winter of his years he still had it. Though I was saddened to hear of his passing, I can at least console myself with the luck that I was able to enjoy the fruits of his passion and dedication to art firsthand. The world is a lesser place without him.

The jazz world has lost yet another link to the so-called glory days, but that sentiment sells Moody short as a musician and a man. In 2002 I came home to Miami from the University of Florida one weekend in October to see Moody play a guest concert with the University of Miami Concert Jazz Band. He killed it that night. Playing with the energy of a man less than half his age, his beaming wit was clearly evident in his playing. My memory of the night is hazy, but I do remember being blown away by a rendition of Body and Soul, played with the Miami faculty ensemble to open the evening. I left Gusman Hall in Coral Gables floored by his performance; as a septuagenarian he played with fire, precision, and levity which most of us couldn't dream of pulling off. Even in the winter of his years he still had it. Though I was saddened to hear of his passing, I can at least console myself with the luck that I was able to enjoy the fruits of his passion and dedication to art firsthand. The world is a lesser place without him.

07 December 2010

Review: Solo

Vijay Iyer

The solo album has long been an obligatory statement of artistic mastery for jazz pianists. Though there have been slight tweaks to the format (see for instance Bill Evans' Conversations With Myself or Charles Mingus' Mingus Plays Piano), it remains relatively unchanged: equal parts original tunes and standards that the pianist can stretch and mold into entirely new creations. I can't think of any major pianist over the age of 35 who has not released a solo album, it seems like one cannot be taken seriously as a jazz master without taking the plunge into unaccompanied expression. In his electronic press kit accompanying the album, Iyer called the project "the ultimate reveal," and "the most personal statement I could possible issue." I couldn't agree more. It is also a big risk. Not even Sonny Rollins can escape accusations of a subpar solo album (I know, bad analogy, since Sonny is a saxophonist and the solo album hasn't hurt his legacy). Upon multiple listens, though, I don't think Iyer has to worry about that.

In the past decade, one additional component has made its way into the solo piano album: the pop cover.* On Solo, Iyer chose to lead the album off with his version of Michael Jackson's Human Nature. I'm not much of a Micheal Jackson fan (which apparently is heresy for someone of my age, but whatevs), and Human Nature is not one of the MJ tunes I would ever throw on my iPod, but I do enjoy Iyer's rendition.

Iyer commences with a dazzling version of Thelonious Monk's Epistrophy, trading in Monk's easy swing for an intense, driving syncopation. The melody of Epistrophy, featuring Monk's trademark chromaticism, has a touch of drama, but Iyer accentuates the dramatic. His left hand is especially heavy, while the right moves at a breakneck pace. It is by far the most exhilarating version of the tune I have heard, and repeated listens have not made the excitement fade. The first third of the album concludes with two more standards, the DeLange/Van Heusen classic Darn That Dream and Duke Ellington's showpiece for Bubber Miley and Tricky Sam Nanton, Black and Tan Fantasy. Black and Tan, with its plungered trumpet and trombone duet, is an especially odd choice for solo piano. How can a rigid instrument match Miley's manipulation of the trumpet which approaches the sound of the human voice? Iyer opts to play the tune as Ellington might have played it, in a dirge-like stride style reminiscent of Ellington's hero, Willie "The Lion" Smith. The result allows the tune itself to take center stage. Iyer is content to allow the harmonies shine, and his adherence to the stride style in his version manage to open up a rich world of improvisation without making the tune sound quaint.

Iyer bookends the album with another Ellington composition, Fleurette Africaine, followed by One For Blount, a blues dedicated to Sun Ra. As with Black & Tan Fantasy, Iyer plays the melody of Fleurette Africaine relatively straight, content to marvel at the beauty of Ellington's harmony. Iyer accentuates the ironic darkness of the melody, giving added weight to the tune. It is an underrated piece of the Ellington canon, and I'm glad Iyer decided to record it.

As captivating as his versions of other people's tunes are on Solo, it is Iyer's originals, covering the middle third of the album, which really shine. As with much of his other work, these tunes are highly improvisational but push the boundaries of postbop (in some cases ignoring them completely). Prelude: Heartpiece is an exploration of consonance and dissonance, comprised of a simple three-note phrase over a pulsing bass line, alternately building and releasing tension. It is followed by Autoscopy, a frantic composition of startling energy that is half Cecil Taylor energy, half ostinato. Iyer shocks you to attention, then lulls you into a peaceful slumber which segues into Patterns, the highlight of the album in my mind. Iyer slowly constructs the main theme, sustaining individual notes of the melody for the first 90 seconds before stating the melody. The independence of the right hand from the left is astonishing, against a sequence of triplets in the treble clef, Iyer plays a syncopated staccato rhythm with his left hand that both disrupts and propels the melody. This accompaniment persists in some form or another throughout the tune, grounding Iyers flights across the keyboard and giving a thematic unity to the eight-minute piece which sounds more like a multimovement suite than a single tune. At times calmly melodic, at others reflecting Iyer's scientific background through the exploration of fractured motifs, it is a microcosm of the album, fulfilling Iyer's characterization of "the ultimate reveal."

Bonus Material: EPK

Personnel: Vijay Iyer, piano

Track Listing: Human Nature; Epistrophy; Darn That Dream; Black and Tan Fantasy; Prelude: Heartpiece; Autoscopy; Patterns; Desiring; Games; Fleurette Africaine; One For Blount

*This is not entirely new, since pianists playing Tin Pan Alley tunes in the postwar years were playing pop tunes. In this context, a pop tune refers to a non-Tin Pan Alley song written in the recent past (e.g. Jason Moran's version of Planet Rock).

06 December 2010

Dave Brubeck

Dave Brubeck turns 90 today, so I'll be listening to Time Out while I make dinner this evening. Two years ago, I wrote this about his landmark 1959 album Time Out:

The time-signature experiments of Time Out were never extrapolated by anyone else the way Miles Davis' modal experiments on Kind of Blue or Ornette Coleman's breaking of harmonic barriers on The Shape of Jazz To Come were. Perhaps this is why it given secondary position to these other works in The Jazz Tradition. Remove the nonstandard time signatures, and the album is still enjoyable, but is not progressive, in the sense that it did not present a drastically new way of playing jazz for other musicians to draw on and evolve. It is still full of surprises, and presents new layers upon further listening, but in the constructed Jazz Tradition, it does not provide trajectory, save for introducing the music to thousands of suburban college students (which is no small feat indeed).Read the whole piece here. Happy birthday, Dave.

02 December 2010

Grammy Awards

Grammy Award nominations came out this week, and while I usually wouldn't bother, it is worth noting that Esperanza Spaulding was nominated for Best New Artist. While I doubt she'll win (the award will probably go to Justin Bieber or Drake, unfortunately), at least The Recording Academy is taking jazz seriously, and not fully ghettoizing the music in its own category. Chalk up a point for the "Jazz is not dead, it just smells funny" camp. You can view the jazz nominations here.

23 November 2010

Almost Back

Quick life announcement: I am heading back to school next year to pursue an MBA, so for the past month or so I've been swamped in B-school applications. I'm almost through, though, and will be back to blogging when the applications are done. In the meantime, check out this version of Nick Drake's Three Hours recorded by the Jason Parker Quartet on their recent tour. Jason recently reposted it to his blog, and it is a wonderful rendition, featuring a beautiful bass solo by Evan Flory-Barnes and some great trumpet work from Jason (dig the half-valve effect starting at 3:54, when Jason's horn starts to sound like an overdriven guitar amp).

Jason is currently working on a rearrangement of Drake's debut album, Five Leaves Left, for his band, and he is hoping to finance the project using a Kickstarter campaign. You can read more about the project at Jason's blog, or you can pledge your financial support for the project here. Jason is not afraid to try any method of financing his various musical projects, and he has seen some great successes with his fan-supported efforts. Help him keep up the good work and support his collaborators as well. You'll get to enjoy the music and the smug feeling of superiority when you tell all your friends about the independent artists who benefit from your largess. It's a win-win!

10 November 2010

A Random Thought

Sometimes when I hear a Lee Morgan solo, I wonder if I will ever be fortunate enough to create something so perfect. It's a lofty aspiration.

07 November 2010

Review: Introducing Triveni

Avishai Cohen

Introducing Triveni

Introducing Triveni

It seems like every other album I've been listening to lately has been either a sax-bass-drums or piano-bass-drums trio. Finally I get some variety, in the form of a trumpet-bass-drum trio, no less. All kidding aside, I cannot find many examples of the trumpet-led pianoless trio (though Miles Davis' second quintet comes close, since Herbie Hancock sometimes sat out during Miles' solos). But the new album from Israeli-born Smalls-bred trumpeter Avishai Cohen is a refreshing statement of neobop which avoids cliche and stays interesting on multiple listens.

It seems the model for his band is not another trumpet player's group, but the early-1960s ensembles of Sonny Rollins and John Coltrane (Cohen covers Trane's Wise One and many of the scaler lines in his solos remind me of Sonny Rollins). The title of the album is a Sanskrit word meaning the confluence of the three holy rivers in the hindu tradition, the physical rivers Ganges and Yamuna, and the mythic Saraswati River. In Cohen's ethos, the Triveni are hard bop, funk, and the avant-garde, the three dominant strains of postwar American jazz.

Cohen's trio, which includes bassist Omer Avital and drummer Nasheet Waits, is well versed in the three styles alluded to in the album's title, and in most cases weave them together relatively seamlessly. On their version of Don Cherry's Art Deco, the group opens with a freeish take on Cherry's melody before moving into a more straightahead feel. Though playing a tune written two decades ago and referencing subgenres who saw their heydays years before that, the three sound totally of the moment. In doing so, they manage to avoid becoming a nostalgia act, which you should know by now is my biggest pet peeve.

Avishai Cohen - Art Deco

Cohen's got chops. He can make the kind of dexterous runs across partials reminiscent of Freddie Hubbard's 1960s output. Though his lines seem very familiar at times (I swear I've heard Sonny Rollins play them before), he manages to sound fresh despite the familiarity. This is a very enjoyable album. I might not remember it well in two or three years, but in the month or so I've had this album in my iPod, I've enjoyed it more with every listen.

It seems the model for his band is not another trumpet player's group, but the early-1960s ensembles of Sonny Rollins and John Coltrane (Cohen covers Trane's Wise One and many of the scaler lines in his solos remind me of Sonny Rollins). The title of the album is a Sanskrit word meaning the confluence of the three holy rivers in the hindu tradition, the physical rivers Ganges and Yamuna, and the mythic Saraswati River. In Cohen's ethos, the Triveni are hard bop, funk, and the avant-garde, the three dominant strains of postwar American jazz.

Cohen's trio, which includes bassist Omer Avital and drummer Nasheet Waits, is well versed in the three styles alluded to in the album's title, and in most cases weave them together relatively seamlessly. On their version of Don Cherry's Art Deco, the group opens with a freeish take on Cherry's melody before moving into a more straightahead feel. Though playing a tune written two decades ago and referencing subgenres who saw their heydays years before that, the three sound totally of the moment. In doing so, they manage to avoid becoming a nostalgia act, which you should know by now is my biggest pet peeve.

Avishai Cohen - Art Deco

Cohen's got chops. He can make the kind of dexterous runs across partials reminiscent of Freddie Hubbard's 1960s output. Though his lines seem very familiar at times (I swear I've heard Sonny Rollins play them before), he manages to sound fresh despite the familiarity. This is a very enjoyable album. I might not remember it well in two or three years, but in the month or so I've had this album in my iPod, I've enjoyed it more with every listen.

Track Listing: One Man's Idea; Ferrara Napoly; Art Deco; Mood Indigo; Wise One; Amenu; You’d Be So Nice To Come Home To; October 25th

Personnel: Avishai Cohen, trumpet; Omer Avital, bass; Nasheet Waits, drums

27 October 2010

S. Neil Fujita

S. Neil Fujita, the graphic designer whose work was featured on album covers for Dave Brubeck's Time Out, Miles Davis' Round About Midnight, and Charles Mingus' Mingus Ah Um, passed away last weekend. The New York Times has a lengthy obituary. Fujita also designed book jackets for The Godfather, In Cold Blood, and many others. Though you may not have heard of him, you are undoubtedly familiar with his work.

21 October 2010

19 October 2010

Marion Brown

Alto saxophonist Marion Brown, a much loved member of the 1960s jazz avant garde, passed away last week. Peter Hum writes a nice remembrance here. I got my first taste of Brown's music from Destination Out, I'm sure there will be a tribute up at that site soon.

On an unrelated note, you may have noticed my absence lately. I've been working on some projects that have sucked up much of my free time lately, so blogging will likely remain sporadic through November.

On an unrelated note, you may have noticed my absence lately. I've been working on some projects that have sucked up much of my free time lately, so blogging will likely remain sporadic through November.

01 October 2010

30 September 2010

Bilal on the Sound of Young America

It's not often my favorite podcast/public radio program tackles jazz, so embedded below is Jesse Thorn's interview with neo-soul singer Bilal, who you may remember from Robert Glasper's excellent 2009 album Double Booked.

Also, check out Bilal's take on Body and Soul (beginning at the 48:30 mark with Glasper at Jazz a la Villette 2010, via Nextbop:

Also, check out Bilal's take on Body and Soul (beginning at the 48:30 mark with Glasper at Jazz a la Villette 2010, via Nextbop:

28 September 2010

PSA

Jamire Williams' band ERIMAJ has a free EP out, Memo to All. Get it. From the album's Bandcamp page:

The Memo To All EP is a retro, progressive, cinematic piece of work brought to you by world-renowned drummer Jamire Williams and his acclaimed new band ERIMAJ. This is only a brief synopsis of what's to come with the full length album scheduled for release first quarter of 2011. This is the memo to all, rather the wake up call to keep your eyes and ears open for the force that is ERIMAJ. Press play and let the tape roll...It's a thoroughly enjoyable collection of heterodox tunes, channeling funk, Miles-era fusion, and hip hop. And come on, it's free. Thanks, Jamire!

Genius

The MacArthur Foundation has announced its annual genius grants, and among the recipients are pianist Jason Moran, who joins fellow jazz musicians Ornette Coleman, Miguel Zenon, and John Zorn as recent recipients. I certainly won't quibble with the selection, and can't wait to see what kind of project Moran creates with his grant money ($500,000).

From the MacArthur Foundation:

From the MacArthur Foundation:

Also receiving a genius grant was David Simon, creator of The Wire and Treme. If you did not watch the first season of Treme, be sure to catch it when it comes out on DVD.

25 September 2010

Jaco Pastorius On South Florida

From a 1977 Downbeat profile reposted at Groove Notes and jacopastorius.com:

"There's a real rhythm in Florida," Jaco Pastorius says in a voice saturated in matter-of-fact. "Because of the ocean. There's something about the Caribbean Ocean, it's why all that music from down there sounds like that. I can't explain it, but I know what it is." He pauses to unclasp his hands, like gangly sandcrabs, and drop his lanky arms to the sides of his lanky body. "I can feel it when I’m there." The concept of Florida is not a constant among Americans. Some people think of Miami Beach, others warm to the less hectic conjuration of Ft. Lauderdale or sleepy St. Petersburg; for some it is the gateway to the new frontier represented by Cape Canaveral, for others the far older frontier that is the Everglades. Still others revel in the broad paradox of a mecca for retirees on the site of Ponce de Leon's Fountain of Youth, or the full-circle irony of a land discovered by Spaniards being gradually inundated by the Spanish-speaking. But no one thinks of Florida as a source of American music. No one thinks of it for jazz.Read the full article here. Jaco and I came of age in completely different South Floridas, but even so his words make me look back fondly on the community where I grew up.

"The water in the Caribbean is much different from other oceans," Jaco says. "It's a little bit calmer down there; we don't have waves in South Florida, all that much. Unless there's a hurricane. But when a hurricane comes, look out, it's more ferocious there than anywhere else. And a lot of music from down there is like that, the pulse is smooth even if the rhythms are angular, and the pulse will take you before you know it. All of a sudden, you’re swept away."

24 September 2010

Review: Never Stop

The Bad Plus

I've discovered that it is pretty much impossible for me not to succumb to fan-boy admiration when writing about a Bad Plus album, so I'm going to go ahead and indulge myself with this here review. The Bad Plus have been together for ten years, and despite their (sometimes) treatment as a gimmicky group that covers Nirvana and Black Sabbath, they have attracted a fiercely loyal group of fans who never fail to express their love of the group (mention the band on Twitter sometime, you'll get a ton of replies from people you had no idea listened to jazz). Their latest album, Never Stop, celebrates the trio's tenth year of playing together. Unlike any of the band's past albums, Never Stop is comprised entirely of original tunes, with none of the adventurous covers of pop and rock tunes that were chiefly responsible for much of the trio's buzz in its early days.1

It is indicative of their charms that The Bad Plus can write tunes that evoke the intricate and driving melodies of prog rock icons like Rush or Emerson Lake & Palmer that absolutely hook me. This is all the more notable because I happen to abjectly despise those bands. On Never Stop, Beryl Likes to Dance falls into this category (and the best example of this type of prog-as-jazz tune is And Here We Test Our Powers of Observation from Give). However, the highlight of the album for me is the title track, which shares some of the proggy energy of Beryl (though, as bassist Reid Anderson pointed out in this interview at A Blog Supreme, the tune was actually composed for an Isaac Mizrahi fashion show for which the band performed a live soundtrack).

The Bad Plus - Never Stop by dave6834

Many of the other factors which have come to characterize The Bad Plus are present on Never Stop: the tongue-in-cheek song titles (like My Friend Metatron), obscure signifying (Bill Hickman at Home is written for a legendary stunt driver), the slavish devotion to writing quality melodies (as in The Radio Tower Has a Beating Heart, which repeats a simple rubato melody with growing intensity for the first four minutes before turning the melody into a delightful little vamp for the final minute and a half), and the enthusiastic free jazz experimentation (see especially 2pm). It is as fitting a restatement of purpose as you would expect from a band which, despite criticisms from certain quarters of the critical establishment, has been developing its identity with flair for a solid decade. Here's hoping we can enjoy this group for decades to come.

Bonus Material: the EPK

1I'm actually pretty happy the band decided to eschew covers for this album. I've grown pretty tired of having to explain to my non-jazz-listening friends that The Bad Plus is more than "that jazz band that plays Nirvana tunes."

Track Listing: The Radio Tower Has a Beating Heart; Never Stop; You Are; My Friend Metatron; People Like You; Beryl Loves to Dance; Snowball; 2pm; Bill Hickman at Home; Super America

Personnel: Ethan Iverson, piano; Reid Anderson, bass; Dave King, drums

22 September 2010

Playlist

- Happy Apple - Green Grass Stains on Wrangler Jeans

- The Bad Plus - Never Stop

- Dave Holland Octet - How's Never?

- Jason Moran Bandwagon - Crepescule With Nellie

- Polar Bear - Bap Bap Bap

- Christian Scott - American't

- Medeski Martin & Wood - Dollar Pants

- Joe Lovano Us Five - Powerhouse

- John Coltrane - Your Lady

- Robert Glasper - Maiden Voyage/Everything In Its Right Place

14 September 2010

Sonny and Ornette

Lest you forget that the modern world is a wonderful place, here is a video from Friday night's Sonny Rollins birthday extravaganza with special guest Ornette Coleman. Roy Haynes is on drums, Christian McBride is on bass. Read Jason Crane's review of the evening here.

11 September 2010

Weekend Reading

Fall is coming...

- Seb reviews Icons Among Us at Nextbop, and I pop up in the comment thread (read my review of the film here).

- Patrick J gives us some extended liner notes to the new Bad Plus album via and interview with the band. You can preview the album at NPR Music. It is all killer, no filler.

- Also at NPR, Patrick wants you to know that you too can like jazz.

- Search and Restore has an audio interview with Vijay Iyer up, discussing his latest album (Hot House review forthcoming) and more. Vijay also provides a mixtape at the end of the interview.

- Finally, an NPR Tiny Desk Concert with the Nels Cline Singers:

09 September 2010

It's About That Time

Via the sports media blog Awful Announcing, here's New Orleans' own Trombone Shorty playing the NFL on NBC theme:

The NFL kicks off tonight, with Shorty's New Orleans Saints hosting the Minnesota Vikings. Back to the music, the NFL on NBC theme is my favorite sports television theme of the moment, only surpassed by the now defunct NBA on NBC theme written by John Tesh (!):

Game on.

07 September 2010

04 September 2010

An Unoriginal Lament Concerning Technology

The other night, I was laying in bed reading while listening to Vijay Iyer on my iPod, and I began thinking about our changing relationship with music. This is by no means an original thought, but our relationship with recorded music has moved from the physical realm to an ethereal space which eludes definition. Until a few years ago, we experienced recorded music through physical objects; acetates, vinyl, reels, cassettes, and CDs, among other media. While these physical artifacts did not necessarily enhance our appreciation of the music contained therein (though in many cases I would argue they did, but more on that some other time), because they required work to obtain, they became part of our identity. The first generation of jazz critics were record collectors. Because early recordings of jazz were so difficult to obtain (record stores of the time did not keep much of a back catalogue, and big box music stores had yet to take root), a network of record-collecting magazines and newsletters became necessary for collectors and enthusiasts to share information and discuss the records they had worked so hard to track down. The vast collections of these jazz nerds (the first jazz nerds, long before Jason Marsalis distorted the badge of identity) became part of the collectors' identity, physical relics of their slavish devotion to the music they loved so much.

Some of Dad's records, in my living room

This pattern of music collection as identity repeated itself as new media came and went, and it was not limited to jazz. Eric Clapton, Jimmy Page, and other figures of the British Invasion collected pressings of American blues musicians. Early hip hop DJs wore out their copies of Funkadelic records. You could tell a lot about a person by looking at their record or CD collection. These were often displayed in prominent places in someone's home, where guests could see right away what their host was listening to. If you ever got bored at a party, you could take a look through the host's music, and usually you would find something of interest, an album you had never heard of, an album you would have never guessed the host would own, one of your favorite albums which might serve to spark a conversation later on. Looking through someone's record collection allowed you to get to know that person in almost an instant.

This pattern of music collection as identity repeated itself as new media came and went, and it was not limited to jazz. Eric Clapton, Jimmy Page, and other figures of the British Invasion collected pressings of American blues musicians. Early hip hop DJs wore out their copies of Funkadelic records. You could tell a lot about a person by looking at their record or CD collection. These were often displayed in prominent places in someone's home, where guests could see right away what their host was listening to. If you ever got bored at a party, you could take a look through the host's music, and usually you would find something of interest, an album you had never heard of, an album you would have never guessed the host would own, one of your favorite albums which might serve to spark a conversation later on. Looking through someone's record collection allowed you to get to know that person in almost an instant.

So instead of showing people my record collection, I write this here blog. It's a bit more work, and it does not even begin to capture the entirety of my taste as well as a record collection could. But it's a start.

Some of Dad's records, in my living room

This pattern of music collection as identity repeated itself as new media came and went, and it was not limited to jazz. Eric Clapton, Jimmy Page, and other figures of the British Invasion collected pressings of American blues musicians. Early hip hop DJs wore out their copies of Funkadelic records. You could tell a lot about a person by looking at their record or CD collection. These were often displayed in prominent places in someone's home, where guests could see right away what their host was listening to. If you ever got bored at a party, you could take a look through the host's music, and usually you would find something of interest, an album you had never heard of, an album you would have never guessed the host would own, one of your favorite albums which might serve to spark a conversation later on. Looking through someone's record collection allowed you to get to know that person in almost an instant.

This pattern of music collection as identity repeated itself as new media came and went, and it was not limited to jazz. Eric Clapton, Jimmy Page, and other figures of the British Invasion collected pressings of American blues musicians. Early hip hop DJs wore out their copies of Funkadelic records. You could tell a lot about a person by looking at their record or CD collection. These were often displayed in prominent places in someone's home, where guests could see right away what their host was listening to. If you ever got bored at a party, you could take a look through the host's music, and usually you would find something of interest, an album you had never heard of, an album you would have never guessed the host would own, one of your favorite albums which might serve to spark a conversation later on. Looking through someone's record collection allowed you to get to know that person in almost an instant.When my dad finally decided to get rid of the records he had been storing for three-plus decades, he let me look through them and keep whatever I wanted. Of the 300 or so albums he had, I kept about a third, mostly albums he had bought in high school and college (Beatles, Jimi Hendrix, Cream, etc.). Though I rarely listen to these records, they have sparked many a conversation with my dad that eventually veer off into discussions of history, culture, politics, etc. But more than that, these records, which I've moved to three different apartments in the past five years, give me a connection to my dad for which I cannot think of an analog. They are in many ways a physical representation of himself, sitting in my living room, always there. I can call him anytime, but the records give him a presence in my life that a cell phone simply cannot.

A music collection in the 20th century

Of course, such a paradigm is largely a thing of the past. The people who buy new music on vinyl are an infinitesimal minority. And the replacement for this technology, digital music, is not physical at all. You could store your entire music collection on a hard drive on your desk. And forget about displaying your music. No one looks through someone else's iTunes library, and even if they did, it's not nearly as fun as thumbing through a record rack. Digital music is much easier to acquire, share, and transport than CDs or records, but these advantages are gained at the expense of our physical relationship with the music we own. Music is no longer a thing we can hold, nor is it something we can literally point to as an identifier of the self. This is not necessarily bad or worse, since the tradeoff has its advantages (especially when it comes to portability). But it does leave us with one less easy signifier of identity, which is not easy to replace. So instead of showing people my record collection, I write this here blog. It's a bit more work, and it does not even begin to capture the entirety of my taste as well as a record collection could. But it's a start.

03 September 2010

Friday Album Cover: Alternate Universe

Jazz and Design linked to some alternate covers to classic jazz recordings by Jeff Rochester this morning, including the version of Cannonball Adderley's At The Lighthouse below. See more of his work, including a delightfully minimalist Blood on the Tracks cover, here.

25 August 2010

15 August 2010

Herman Leonard

Another member of the family has left us this weekend. Photographer Herman Leonard, whose work you have seen many times possible without even knowing it, has passed away. Read the New Orleans Times-Picayune obituary here. The photo of Dizzy Gillespie on the right side of the page is hanging in my apartment, and is one of my favorite works of jazz photography. Leonard's photos had wonderful depth and texture, you can practically feel the smoke in Royal Roost while looking at the photo.

Mark Myers interviewed Leonard last year, and Leonard said of his photos, "I wanted to preserve the mood and atmosphere as much as possible. My goal was to capture these artists at the height of their finest creative moments." He did just that, and those of us too young to have seen Parker and Gillespie and Ellington and Fitzgerald at the time will be forever indebted to Herman Leonard.

Image via AllPosters.com

Mark Myers interviewed Leonard last year, and Leonard said of his photos, "I wanted to preserve the mood and atmosphere as much as possible. My goal was to capture these artists at the height of their finest creative moments." He did just that, and those of us too young to have seen Parker and Gillespie and Ellington and Fitzgerald at the time will be forever indebted to Herman Leonard.

Image via AllPosters.com

14 August 2010

Abbey Lincoln

Today we lost one of the true originals. Abbey Lincoln passed away today in New York. Read Nate Chinen's obituary here. I will let others eulogize her, since I am not terribly well-versed in her work. Still, her early-1960s output included some real gems, beginning with the classic Straight Ahead, but also including her contributions to (then-husband) Max Roach's Freedom Now Suite and Percussion Bitter Sweet. She sang with a fire and passion befitting her era, and was unafraid to assert herself, both as an African American in a country where she did not yet enjoy equal rights and as a woman in a male-dominated jazz world. The world is worse off without her voice, but at least she left us with some brilliant recordings.

Image via Pieter Boersma

Image via Pieter Boersma

12 August 2010

This and That

Nextbop posted this promo clip of ERIMAJ, Jamire Williams' band. It sounds great, and I for one will be anxiously awaiting the EP due out soon.

Kottke posted this Betty Boop cartoon featuring Cab Calloway singing St. James Infirmary today:

I also really dug Antoine Batiste's improptu a capella version on Treme earlier this year (sung impeccably by Wendell Pierce). Unfortunately, I couldn't find it on YouTube, so here's fellow Treme star Kermit Ruffins, in which he works in Calloway's Minnie the Moocher before the clip fades out:

08 August 2010

Programming Note and Links

Posting will be light in August. I've got a few extra things on my plate at the moment that require most of my time, but I'll pop in from time to time and get back up to speed in September. Here are a few things to check out today while you're trying to escape the heat.

- It's Newport time again, and NPR is streaming some of today's performances, including Matt Wilson, Dave Douglas' Brass Ecstasy, John Faddis, and the Wynton Marsalis-Dave Brubeck collaboration. Yesterday's action included Fly, Darcy James Argue's Secret Society, and the JD Allen Trio.

- Also at NPR this week, Patrick J. nerds out to some Guillemo Klein. Great stuff.

- Fred Kaplan discusses the recent onslaught of audiophile pressings of classic Blue Note albums in the New York Times today.

- Finally, Andrew Durkin shares a choice quote about technique and improvisation. Spot on.

- Finally, George Wein spoke to Mark Myers recently about the 1960 Newport Rebel Festival, which spawned an unlikely collaboration on record featuring Charles Mingus, Max Roach, Eric Dolphy, Jo Jones, and Roy Eldridge, among others.

Photo: JD Allen at Newport via NPR

30 July 2010

Juke Joint

This color photo of a juke joint in Belle Glade, Florida comes via the Denver Post's photo blog, which just ran a post featuring 70 color photographs from 1939-1943. The photos are from the Farm Security Administration and Office of War Information archives. Be sure to check out the full post.

27 July 2010

The Latest Iteration of the Jazz Audience Debate

Point:

In addition to treating music as sound rather than art, Generation F rarely listens to an entire track, let alone an entire album. The record industry has been grappling with this album problem since the arrival of the digital download. Buyers cherry pick what they want for 99 cents rather than purchase entire albums. Which means most personal iTunes libraries are vessels for thousands of individual songs. Melody fatigue sets in fast and fingers commonly click for the next song before a track is through.Counterpoint:

"...and its history is too deep for a casual relationship." I could say the same about heavy metal. But I wouldn't, because I'm not a snobbish idiot. Music is music. Each work should be taken or left on its own merits. This is the single thing I hate most about jazz people—their fixation on the idea that jazz is a course of study, not a world of music there to be enjoyed. Not studied, though you can do that if you want to. Enjoyed. Jazz musicians, like all musicians, make music in the hope that it will give people pleasure, not in the hope that it will give people subjects for monographs and symposia decades later. This is why I say that if you want to convert a non-jazz listener into a jazz listener, don't say "You should listen to jazz." Instead, figure out what they already like, and say, "You should listen to [specific jazz album]."Addendum:

It's a good thing Myers' complaining is mostly directed at people his own age or older. If people in their twenties read his whiny bullshit and reductive generalizations of their generation, they might wind up turned off to jazz, rather than mostly unaware of it, as they are now.

Myers' logical leap is his assumption that my generation will never approach music listening in any other way. Just because you treat music as white noise at times, or have an itchy trigger finger at others, certainly doesn't mean that you're incapable of close listening. (If nobody ever shows us how to do that close listening, it seems like the fault of music education rather than technology.) After all, the same innovations that Myers believes to encourage bad things in listening — the MP3, Apple's music software, tiny portable players — also make it possible to pay more attention in more ways and means than ever too.There's not much that I feel the need to add here, except to echo Freeman's and Jarenwattananon's assertions that when discussing the state of the jazz audience, technology is a double-edged sword. Pick a medium, and you can point out advantages and disadvantages over other media. If anything, the rise of digital media has been a net positive for expanding the jazz audience, for these reasons (among others):

- Digital media lowered the price of jazz albums. Music that would cost $17.99 at Barnes and Noble in the late 1990s can be purchased on iTunes of the Amazon mp3 store for $9.99 or less. During the CD era, jazz albums were largely priced and marketed as kind of a luxury good, since most of the audience was middle-aged (or older) and relatively affluent. This made it more difficult for younger audiences to get their hands on as much music as possible.

- Illegally downloaded music, while bad financially for both record companies and artists, nonetheless put jazz music in more young people's collections. When I was in college, I noticed that more than a few non-jazz fans I knew had some jazz on their hard drives. It cannot be a completely bad thing for more people to have access of the music, even if it took illegal means to achieve that end.

- Digital media gave projects like Nextbop a chance to succeed in convincing young people that, despite what preconceived notions they have about jazz, they may actually like it. Nextbop could not exist in the LP era.

Something Different

No jazz today, just Best Coast. Fuzzy, lo-fi shoegaze with a nod to the Beach Boys and the Ronettes:

Their new album drops today.

26 July 2010

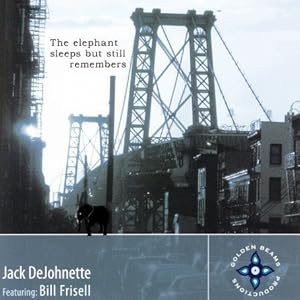

Under the Radar: The Elephant Sleeps But Still Remembers

Jack DeJohnette featuring Bill Frisell

The Elephant Sleeps But Still Remembers

When some albums go out of print, I mourn for those who will miss their chance at hearing them. Such is The Elephant Sleeps But Still Remembers, an exploratory gem from Jack DeJohnette and Bill Frisell. Fulfilling his reputation as an adventurous spirit, DeJohnette masterminds an effort worthy of its own entry at destination: OUT. The album was recorded at the 2001 Earshot Festival in Seattle, with bass lines, effects, ambient sounds, and loops added by DeJohnette and sound engineer Ben Surman in post-production.

The tunes on The Elephant Sleeps But Still Remembers fall into two categories: grooves and explorations. The title track falls in the former. Leading off the album, Bill Frisell lays down a spooky extended blues over DeJohnette's heavy rhythms. The effects in the background give the tune a darker, more animated mood which really enhances the tune. Frisell and DeJohnette play so well off each other, with one seamlessly filling the gaps left over by the other. The song is followed by Cat and Mouse, a tune in the latter category on which DeJohnette plays various percussion and finger keyboards while Frisell picks some free banjo. It is very outside, I think Frisell plays banjo here the way Don Cherry plays trumpet. It is nonsensical in a way but also very fun to hear. Frisell's playfulness shines through.

Another such sound exploration comes on Cartune Riots. I really can't tell who is doing what on this track, but it sounds like an alternate universe in a Marvin the Martian tune which may or may not give you nightmares and maybe flashbacks. It will turn off many listeners, to be sure, but I appreciate the effort.

One of Frisell's strengths is his sense of melody, which allows him to craft solos full of little ideas from the same harmonic palette. This is evident in Ode to South Africa, the highlight of the disc. Frisell plays about six minutes in F major, but he doesn't repeat himself and doesn't dwell on one motif for more than sixteen measures or so. Under him, DeJohnette demonstrates that the drumset was originally a recreation of an African drum ensemble. He moves from an exploration of the toms into a robust 4-4 groove on ride cymbal and open snare. Frisell's solo builds up to a feeling of euphoria which accompanies a loop of African voices that echo through the final ninety seconds of the tune. Of all the Frisell solo's I've heard, I think this one is my favorite.

The album closes with John Coltrane's After the Rain, and DeJohnette and Frisell accomplish the feat of reworking a Coltrane tune so well that I prefer it to the original (which rarely happens). Switching to piano, DeJohnette augments the melody with some whimsical lines on piano to give the tune a dream-like haze. Combined with Frisell's spare comping, it's the perfect cool-down. Like a post-coital nap, it is a calming restoration of the senses which leaves the listener completely at peace. Serenity now.

Track listing: The Elephant Sleeps But Still Remembers...; Cat and Mouse; Entranced Androids; The Garden of Chew-Man-Chew; Otherworldly Dervishes; Through the Warphole; Storm Clouds and Mist; Cartune Riots; Ode to South Africa; One Tooth Shuffle; After the Rain

Personnel: Jack DeJohnette: drums, percussion, vocals, piano; Bill Frisell: guitar, banjo; Ben Surman: additional percussion

25 July 2010

Sunday Morning

In case you missed it, Karen Michel interviewed Dave Holland yesterday for NPR's Weekend Edition yesterday. The story is worth the time, covering Holland's "discovery" by Miles Davis, his development as a bassist, and his mentoring of younger musicians.

I recently got my hands on Holland's new album, Pathways. I've enjoyed it both times I listened to it so far, but may not be returning to it too much. Not because the music isn't good. It is. I'm just not in a mood for an eight-piece ensemble at the moment. Regardless, the rendition of How's Never on the album is pure bliss, and Nate Smith is an absolute titan of a drummer, and when is Chris Potter ever boring? (hint: never). Holland has become such an institution in jazz that he can release a quality album like Pathways and I will take it for granted. You have to make some incredible music for a really long time to make that happen.

23 July 2010

Friday Album Cover: Rubber Soulive

This week I learned via Nextbop that acid jazz trio Soulive will release a Beatles tribute in September titled Rubber Soulive. The cover for the album (above), is a wonderfully minimalist homage to the distinctive psychedelic font found on the Beatles' Rubber Soul (below). While I don't yet know whether I will like the album, I wholeheartedly approve of the cover.

17 July 2010

Icons Among Us

Icons Among Us: Jazz in the Present Tense

"The truth never remains the same... The truth is now." So says Nicholas Payton at the outset of the DVD version of Icons Among Us, the documentary of modern jazz which has sparked much discussion in the jazz world over the past year. The film searches for an answer to the question which has sparked so many blog posts: What is jazz, or more specifically, what is jazz today? Those looking for a definite answer to this question will be disappointed by the film, but the meandering discussion, culled from interviews with about fifty different musicians, says a lot.

Jazz has become a music that is united not by certain stylistic tendencies, but by a broad range of traditions which inform, rather than define the music (that, at least, is my best attempt at a definition). The major arguments suggested by the documentary are united by one theme: the limits of codification. Well, almost. Wynton Marsalis, a figure present in any debate about the nature of jazz, makes a few appearances throughout the film, though he doesn't say much that anyone familiar to the debate hasn't heard before. At the beginning of the film, he laments, "We [jazz musicians] try to get as far away from that art as possible." He makes a facile analogy to other recognized art forms, saying, "We're the only people who created an art form and then tried to figure out how to make it not have a definition." While people are still trying to get into what Homer or Dante did, according to Marsalis, modern jazz musicians are running away from the past. Of course, we do not expect modern novelists to write something like The Iliad.

But let's not dwell on Wynton. Though at first glance, Icons Among Us seems like a convention of Nextbop artists, we hear from a number of musicians who you would never expect to share a bill at a festival, including Matthew Shipp, Wayne Shorter, Skerik from Garage a Trois, and Esperanza Spaulding. Unlike Marsalis, most of these artists eschew a reductive take on jazz, and instead argue that in a world where geographic and stylistic boundaries have been collapsed, what matters more than adherence to certain bedrock principles inherent in jazz is a pure expression of the unadulterated self. Most of the musicians in Icons Among Us don't care so much about defining their music. They know that it accurately reflects themselves and that it is not mainstream, and that seems to be enough.

Indeed, it seems the only rule in jazz to most of the musicians we hear from in the film is the emphasis on improvisation. Through improvisation a musician can channel both historical precedents like Bill Evans and Wayne Shorter in addition to other styles that appeal to that particular musician, be it hip hop, Americana, or whatever. By the end of the film, you can listen to performances from Roy Hargrove and the Brain Blade Fellowship, and even though they sound worlds apart, you can't really either of them anything but jazz. Is the argument (such as it is) in Icons Among Us successful? I can't tell, since I am clearly predisposed to this kind of heterodox definition of jazz. But it does show that, small(ish) audience to the contrary, we can at least say that jazz is alive and well, if nothing more.

See also: The Jazz Indie: an icons among us blog

Jazz has become a music that is united not by certain stylistic tendencies, but by a broad range of traditions which inform, rather than define the music (that, at least, is my best attempt at a definition). The major arguments suggested by the documentary are united by one theme: the limits of codification. Well, almost. Wynton Marsalis, a figure present in any debate about the nature of jazz, makes a few appearances throughout the film, though he doesn't say much that anyone familiar to the debate hasn't heard before. At the beginning of the film, he laments, "We [jazz musicians] try to get as far away from that art as possible." He makes a facile analogy to other recognized art forms, saying, "We're the only people who created an art form and then tried to figure out how to make it not have a definition." While people are still trying to get into what Homer or Dante did, according to Marsalis, modern jazz musicians are running away from the past. Of course, we do not expect modern novelists to write something like The Iliad.

But let's not dwell on Wynton. Though at first glance, Icons Among Us seems like a convention of Nextbop artists, we hear from a number of musicians who you would never expect to share a bill at a festival, including Matthew Shipp, Wayne Shorter, Skerik from Garage a Trois, and Esperanza Spaulding. Unlike Marsalis, most of these artists eschew a reductive take on jazz, and instead argue that in a world where geographic and stylistic boundaries have been collapsed, what matters more than adherence to certain bedrock principles inherent in jazz is a pure expression of the unadulterated self. Most of the musicians in Icons Among Us don't care so much about defining their music. They know that it accurately reflects themselves and that it is not mainstream, and that seems to be enough.

Indeed, it seems the only rule in jazz to most of the musicians we hear from in the film is the emphasis on improvisation. Through improvisation a musician can channel both historical precedents like Bill Evans and Wayne Shorter in addition to other styles that appeal to that particular musician, be it hip hop, Americana, or whatever. By the end of the film, you can listen to performances from Roy Hargrove and the Brain Blade Fellowship, and even though they sound worlds apart, you can't really either of them anything but jazz. Is the argument (such as it is) in Icons Among Us successful? I can't tell, since I am clearly predisposed to this kind of heterodox definition of jazz. But it does show that, small(ish) audience to the contrary, we can at least say that jazz is alive and well, if nothing more.

See also: The Jazz Indie: an icons among us blog

12 July 2010

Music Monday

Earlier this year the jazz blogosphere was abuzz over a single (rare in jazz) off the new Christian Scott album. Scott's take on Thom Yorke's The Eraser is a pretty mellow affair, with Scott using a harmon mute to create a wispy, airy tone that I don't think I've ever heard before. Yorke dug it, if we can make that assumption based on the fact that he invited Christian to sit in on one of his side projects recently.

10 July 2010

It's Funny Because It's True

Comedian Paul F. Tompkins on jazz:

| Jokes.com | ||||

| Paul F. Tompkins - Jazz is Lousy | ||||

| comedians.comedycentral.com | ||||

| ||||

Whether you like the bit or not, this guy has clearly listened to some jazz, otherwise he wouldn't know about musicians laughing on stage. Not for nothing, this is Exhibit A in my case for rebranding jazz.

06 July 2010

The King is Dead, Long Live the King

Louis Armstrong died 39 years ago today. Shortly after Armstrong died, Dizzy Gillespie penned this obituary for Satchmo (click to enlarge).

Never before in the history of black music had one individual so completely dominated an art form as the Master, Daniel Louis Armstrong. His style was equally copied by saxophonists, trumpet players, pianists and all of the instrumentalists who make up the jazz picture.Here are the two playing Umbrella Man:

One of the significant factors in his art was the ability to sing exactly as he played. Before Louis, too, the role of the trumpet was to lead. He established the trumpet as a solo instrument. The distinctive quality in his style was POWER. He was known to have hit hundreds of high C's, one after the other, each with the same level, and to end on a high F or G. This was unheard of before. His melodic concept was as near perfect as possible, his rhythm impeccable. And his humor brought joy into the lives of literally millions of people, both black and white, rich and poor.

When the State Department sent me on a cultural mission to Eastern Europe, the Middle East and South America in 1956, the band did a musical history of the various innovations that had been created in our music. Needless to say, Louis was prominently displayed.

Louis is not dead, for his music is and will remain in the hearts and minds of countless millions of the world's peoples, and in the playing of hundreds of thousands of musicians who have come under his influence.

The King Is Dead ... Long Live the King!

Image via Columbia University

02 July 2010

Struttin' With Some Barbecue

I'm off on a mini-vacation to the Eastern shore of Maryland this weekend. I'll be seeing you again next week. In the meantime, drink up, eat well, and remember to celebrate the paterfamilias:

30 June 2010

Yes, Yes, A Thousand Times Yes

I never wrote that promised response to the latest volleys in the jazz wars, but Will Layman touched a nerve in an essay for PopMatters this week, so I may yet chime in. In a review of Icons Among Us (which I'll be reviewing as soon as I can get a copy from NetFlix), Layman lays out the problem facing jazz with elegant simplicity:

For most people, jazz is a dead man's music. This just might be the problem in making jazz a sustainable art form.The whole article is here. It is worth your time this morning. Layman takes a detached stance from the argument that contemporary musicians should break free from the past and even eschew the word jazz, but I am all for it. As Nicholas Payton puts it in the film, "In order to find the way, you must leave the way. You have to be open." I know my view is still in the minority, but regardless, the word "jazz" retains a large amount of cultural baggage which skews most people's perception of the music. If a label is getting in the way of the music, then it may be time to simply invent a new label and move on.

28 June 2010

Music Monday

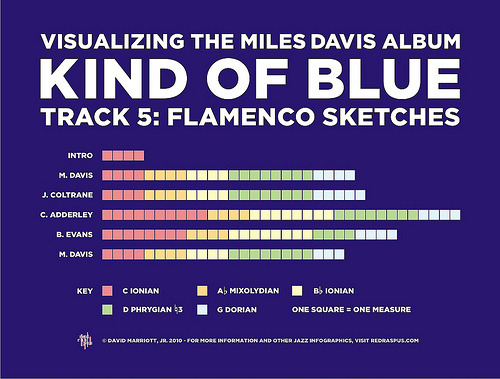

Miles Davis was the first jazz musician whose music I truly loved. I first began discovering his work when my parents bought me a copy of Kind of Blue for Christmas one year. I was 13. Miles is a great first love for any jazz fan, especially since his catalogue spans so many genres and schools of jazz that it serves as a pretty good proxy for the history of jazz between 1944 (his arrival on the New York scene) and 1975 (his first retirement). Miles was present in the first bebop, hard bop, avant-garde (for lack of a better term), and fusion recordings I ever heard.

But over the past few years the album to which I find myself returning again and again is Tribute to Jack Johnson, recorded in 1970 and released in 1971. The album was the result of music Miles produced for a documentary on the early-20th century heavyweight champion. The album featured John McLaughlin, Herbie Hancock, Billy Cobham, Steve Grossman, and Michael Henderson. In his autobiography, Miles doesn't say much about the album, except that he originally wanted Buddy Miles (then playing with Jimi Hendrix) on the album and that it was not adequately promoted by Columbia Records. In his magisterial biography of Davis, So What, John Szwed wrote that Miles passion for and knowledge of boxing helped give the album its sound:

But over the past few years the album to which I find myself returning again and again is Tribute to Jack Johnson, recorded in 1970 and released in 1971. The album was the result of music Miles produced for a documentary on the early-20th century heavyweight champion. The album featured John McLaughlin, Herbie Hancock, Billy Cobham, Steve Grossman, and Michael Henderson. In his autobiography, Miles doesn't say much about the album, except that he originally wanted Buddy Miles (then playing with Jimi Hendrix) on the album and that it was not adequately promoted by Columbia Records. In his magisterial biography of Davis, So What, John Szwed wrote that Miles passion for and knowledge of boxing helped give the album its sound:

His own feel for the movements of a boxer came across clearly in the soundtrack, where he tried to make the rhythms mime the grace and confidence of fighters like Sugar Ray Robinson.Szwed notes that Jack Johnson "was one of Miles' favorite recordings for a long time," which is saying something since Miles was often dismissive of his own work in retrospect. Darcy James Argue sparked my revived interest in Jack Johnson. In this blog post on Davis' 1970s work, Argue remembers when he first heard Jack Johnson, which "blew my head wide open" as a teenager:

I can even pinpoint the exact moment when my brains hit the wall -- it's early in "Right Off" where John McLaughlin drops to Bb, but Michael Henderson keeps going in E, and Miles decides this bitonal no-man's land would be the perfect spot for him to make his entrance. And it is.That moment comes at the 2:12 mark. Check it out below, it will get you through your Monday.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)