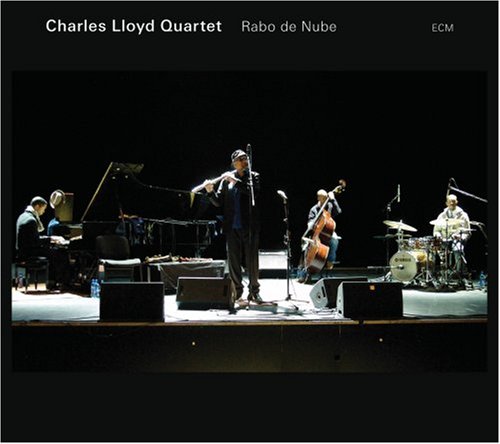

Charles Lloyd Quartet

Rabo de Nube

With so many past masters of jazz passing away these days, I pay attention when an old lion releases a new recording - indeed, morbid as the thought may be, we have no way of knowing if each recording will be that particular musicians' final album. So you can understand why my interest was piqued when I heard that Charles Lloyd had released a live album recorded last year in Europe. Rabo de Nube, his latest offering, serves as a fond look back for Lloyd, in which he and his band run through a series of tunes from various stages of his vast career. Showing the introspective maturity one would expect of a lion in winter, Lloyd constantly pulls moments of surprise and beauty out of some familiar tunes, including "Sweet Georgia Bright," first heard on the 1964 Cannonball Adderley album Fiddler on The Roof. He and his band put into practice Ralph Ellison's dictum that jazz can put people directly in the present moment, where they can reflect on the past while also looking forward.

And what a band it is, with piano wunderkind Jason Moran injecting much energy into Lloyd's frequent sidemen Ruben Rogers and Eric Harland. This quartet lives up to the standard set by Lloyd's past ensembles with Keith Jarrett, Billy Hart, and others, and pushes Lloyd into heady territory. Jason Moran may be the best young pianist in jazz, who already has an impressive discography to his own credit. His uses of complex rhythmic and harmonic devices, combined with his percussive style and historically-minded approach to piano, make this album more than just a blowing session. He and his former schoolmate, Harland, drive Lloyd during his solos. Combined with Lloyd's characteristic warm tone, Harland and Moran balance out the ensemble, giving pulse and drive to Lloyd's Coltrane-inspired melodicism. Rogers, a newcomer to Lloyd's quartet as well, more than holds his own, letting Moran and Harland lead the comping during Lloyd's solos without disappearing behind them. His soloing is also impressive and melodically fresh.

Highlights on this disc include the opening track, "Prometheus," as well as the aforementioned "Sweet Georgia Bright," in which Lloyd and his band let loose. Also of note is "La Colline de Monk," the lead-in to "Sweet Georgia Bright," in which Moran channels Thelonious Monk in new and surprising ways (no small feat), filtering stride foundations and Monkish harmonies through his own inventive rhythms. Moran's monologue on "La Colline de Monk" is emblematic of the album, reworking familiar material with a new approach which challenges the listener and personifies the Ellisonian stance of looking forward while also looking back. Released a few days shy of his seventieth birthday, Charles Lloyd has shown with Rabo de Nube that he is still Charles Lloyd, and his listeners are all the better for it.

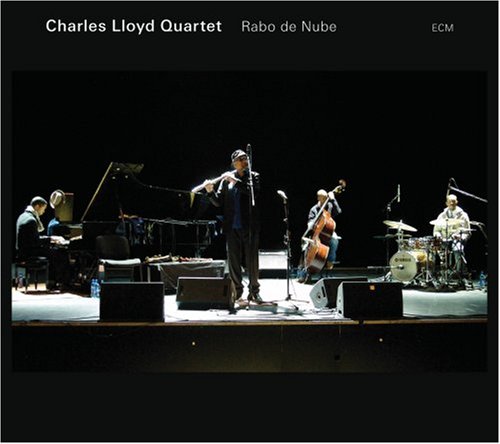

Rabo de Nube

With so many past masters of jazz passing away these days, I pay attention when an old lion releases a new recording - indeed, morbid as the thought may be, we have no way of knowing if each recording will be that particular musicians' final album. So you can understand why my interest was piqued when I heard that Charles Lloyd had released a live album recorded last year in Europe. Rabo de Nube, his latest offering, serves as a fond look back for Lloyd, in which he and his band run through a series of tunes from various stages of his vast career. Showing the introspective maturity one would expect of a lion in winter, Lloyd constantly pulls moments of surprise and beauty out of some familiar tunes, including "Sweet Georgia Bright," first heard on the 1964 Cannonball Adderley album Fiddler on The Roof. He and his band put into practice Ralph Ellison's dictum that jazz can put people directly in the present moment, where they can reflect on the past while also looking forward.

And what a band it is, with piano wunderkind Jason Moran injecting much energy into Lloyd's frequent sidemen Ruben Rogers and Eric Harland. This quartet lives up to the standard set by Lloyd's past ensembles with Keith Jarrett, Billy Hart, and others, and pushes Lloyd into heady territory. Jason Moran may be the best young pianist in jazz, who already has an impressive discography to his own credit. His uses of complex rhythmic and harmonic devices, combined with his percussive style and historically-minded approach to piano, make this album more than just a blowing session. He and his former schoolmate, Harland, drive Lloyd during his solos. Combined with Lloyd's characteristic warm tone, Harland and Moran balance out the ensemble, giving pulse and drive to Lloyd's Coltrane-inspired melodicism. Rogers, a newcomer to Lloyd's quartet as well, more than holds his own, letting Moran and Harland lead the comping during Lloyd's solos without disappearing behind them. His soloing is also impressive and melodically fresh.

Highlights on this disc include the opening track, "Prometheus," as well as the aforementioned "Sweet Georgia Bright," in which Lloyd and his band let loose. Also of note is "La Colline de Monk," the lead-in to "Sweet Georgia Bright," in which Moran channels Thelonious Monk in new and surprising ways (no small feat), filtering stride foundations and Monkish harmonies through his own inventive rhythms. Moran's monologue on "La Colline de Monk" is emblematic of the album, reworking familiar material with a new approach which challenges the listener and personifies the Ellisonian stance of looking forward while also looking back. Released a few days shy of his seventieth birthday, Charles Lloyd has shown with Rabo de Nube that he is still Charles Lloyd, and his listeners are all the better for it.

Track Listing: Prometheus; Migration of Spirit; Booker's Garden; Ramanujan; La Colline de Monk; Sweet Georgia Bright; Rabo de Nube

Personnel: Lloyd, saxophone, flute; Jason Moran, piano; Ruben Rogers, bass; Eric Harland, drums