-

2. Jason Moran Bandwagon: Out Front

Art was driving to an out-of-town job and passed through a village where traffic was completely tied up because of a funeral procession. Since he couldn't get past the cemetery until the service was over, he got out and listened to the eulogy. The minister spoke at length about the virtues of the deceased, and then asked if anyone had anything else to add. After a silence during which nobody spoke up, Art said, "If nobody has anything to say about the deceased, I'd like to say a few words about jazz!"1Such was Blakey, always educating. And he is not the only musician who should be championed for his role as a bandstand professor. Dave Holland has served as a kind of Dean of Postbop for the past 30 years. His working bands, while they lack the brand name of Blakey's Messengers, have nonetheless served as a revolving door of talent which Holland nurtures. Like Blakey, Holland has an impressive record of graduates: Chris Potter, Steve Coleman, Eric Harland, and Kenny Wheeler, to name but a few.

However, this is not to say that Monk does not emerge from the book as a triumphant figure. Kelley does not dispute the importance of Monk in the history of jazz, though he does rightfully critique Monk's complaints during the height of bebop's popularity that he did not get enough credit for his role in the development of the music. In the end, though, Monk seems more like a tragic figure than a triumphant one. While some of his peers like Miles Davis and Dizzy Gillespie thrived in the late-1950s and beyond, Monk frequently studied to make ends meet or even get gigs, on top of his psychological disorder.

However, this is not to say that Monk does not emerge from the book as a triumphant figure. Kelley does not dispute the importance of Monk in the history of jazz, though he does rightfully critique Monk's complaints during the height of bebop's popularity that he did not get enough credit for his role in the development of the music. In the end, though, Monk seems more like a tragic figure than a triumphant one. While some of his peers like Miles Davis and Dizzy Gillespie thrived in the late-1950s and beyond, Monk frequently studied to make ends meet or even get gigs, on top of his psychological disorder. I bought one of my favorite jazz books for $4 at the bargain table at a Barnes & Noble in the late-90s. The Jazz Musician, a collection of interviews with jazz musicians from the 1980s, was compiled from the pages of Musician Magazine (not this one). I would have never found out about had I not seen it on that table; it is one reason why I continue to shop at used book stores. A few excerpts are below after the jump.

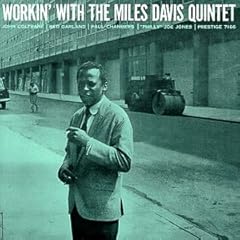

I bought one of my favorite jazz books for $4 at the bargain table at a Barnes & Noble in the late-90s. The Jazz Musician, a collection of interviews with jazz musicians from the 1980s, was compiled from the pages of Musician Magazine (not this one). I would have never found out about had I not seen it on that table; it is one reason why I continue to shop at used book stores. A few excerpts are below after the jump. This weekend's post on Red Garland and Charlie Parker at JazzWax had me reminiscing about the mid-1950s Miles Davis quintet with Garland, John Coltrane, Paul Chambers, and Philly Joe Jones. Back when I was initially exploring jazz in middle school and high school, this band was the first of the canonical ensembles that I fell in love with. Having read a glowing review of Workin' With the Miles Davis Quintet in a book I had, I quickly bought copies of it and three other albums, Steamin', Cookin', and Relaxin', all of which were recorded over two sessions in 1956 as Miles wanted to fulfill obligations with Prestige Records before recording with Columbia. They were among the dozen or so albums that I listened to continually in high school as I developed my taste in jazz. Miles' playing during this period was also a major influence on my jazz improvisation at the time (I was quite taken by his lyricism, and leaned on him heavily as I developed my own sense of melodicism).

This weekend's post on Red Garland and Charlie Parker at JazzWax had me reminiscing about the mid-1950s Miles Davis quintet with Garland, John Coltrane, Paul Chambers, and Philly Joe Jones. Back when I was initially exploring jazz in middle school and high school, this band was the first of the canonical ensembles that I fell in love with. Having read a glowing review of Workin' With the Miles Davis Quintet in a book I had, I quickly bought copies of it and three other albums, Steamin', Cookin', and Relaxin', all of which were recorded over two sessions in 1956 as Miles wanted to fulfill obligations with Prestige Records before recording with Columbia. They were among the dozen or so albums that I listened to continually in high school as I developed my taste in jazz. Miles' playing during this period was also a major influence on my jazz improvisation at the time (I was quite taken by his lyricism, and leaned on him heavily as I developed my own sense of melodicism).Wherever we played the clubs were packed, overflowing back into the streets, with long lines of people standing out in the rain and snow and cold and heat. It was something else, man, man. And a whole lot of famous people were coming every night to hear us play. People like Frank Sinatra, Dorothy Kilgallen, Tony Bennett (who got up on the stage and sang with my band one night), Ava Gardner, Dorothy Dandridge, Lena Horne, Elizabeth Taylor, Marlon Brando, James Dean, Richard Burton, Sugar Ray Robinson, just to mention a few.The band earned this star power, to be sure. Miles remembers "It was so bad that it used to send chills through me at night, and it did the same thing to the audiences, too." Miles had just recently made his mythologized "comeback performance" at the 1955 Newport Jazz Festival, playing Monk's 'Round Midnight to a captivated crowd. He had also kicked his heroin habit just before this period, and he had found a new energy which drove him to conquer the ears of jazz listeners. He had one of the all-time great rhythm sections behind him: The swinging Red Garland on piano, whose block chords and light touch glued the rhythm section; the fiery Philly Joe Jones on drums, who felt what Miles was thinking, and who Miles described as "the fire that was making a lot of shit happen;" and the extremely hip Paul Chambers on bass, who could make quarter notes swing like you could not believe.

Miles Davis made one of his most acclaimed recordings 46 years ago today. On February 12, 1964, Miles Davis and his quintet (then featuring George Colemanon tenor saxophone with the now-legendary Tony Williams-Ron Carter-Herbie Hancock rhythm section) played a benefit at Philharmonic Hall in New York's Lincoln Center for a coalition of civil rights groups including the Student Non-Violent Coordinating Committee, the Congress of Racial Equality, the recording of which (The Complete Concert 1964

Miles Davis made one of his most acclaimed recordings 46 years ago today. On February 12, 1964, Miles Davis and his quintet (then featuring George Colemanon tenor saxophone with the now-legendary Tony Williams-Ron Carter-Herbie Hancock rhythm section) played a benefit at Philharmonic Hall in New York's Lincoln Center for a coalition of civil rights groups including the Student Non-Violent Coordinating Committee, the Congress of Racial Equality, the recording of which (The Complete Concert 1964We just blew the top off that place that night. It was a motherfucker the way everybody played -- and I mean everybody. A lot of the tunes we played were done up-tempo and the time never did fall, not even once. George Coleman played better that night than I have ever heard him play. There was a lot of creative tension happening that night that the people out front didn't know about. We had been off for a while as a band, each doing other things. Plus it was a benefit and some of the guys didn't like the fact that they weren't getting paid. One guy -- and I won't call his name because he has a great reputation and I don't want to cause him no grief, plus he's a very nice guy on top of everything else -- said to me, "Look, man, give me my money and I'll contribute what I want to them; I'm not playing no benefit. Miles, I don't make as much money as you do." The discussion went back and forth. Everyone decided that they were going to do it, but only this one time. When we came out to play everybody was madder than a motherfucker with each other and so I think the anger created a fire, a tension that got into everybody's playing, and maybe that's one of the reasons everybody played with such intensity....And that's just one of the qualities that earned Miles the French Legion of Honor.

Even NPR is not a safe haven from the last volleys of the Jazz Wars, as the comment section of a recent blog post at A Blog Supreme showed. As David Adler points out, the post itself is innocuous, but the comment section quickly spun into a round of contradictory accusations.

Even NPR is not a safe haven from the last volleys of the Jazz Wars, as the comment section of a recent blog post at A Blog Supreme showed. As David Adler points out, the post itself is innocuous, but the comment section quickly spun into a round of contradictory accusations.Why can't jazz still sound like Dexter Gordon? Why does jazz still sound like Dexter Gordon? Why are young musicians so afraid to break the rules? Why are young musicians so heedless of the rules?But this somewhat reactionary tendency to lament the loss of a golden age is not limited to the jazz world. Last week Rachel Maddux asked in the pages of Paste Magazine, Is Indie Dead?. Hey, at least this pathology isn't limited to jazz listeners...