- Why is it necessary to promote jazz as "a national and world treasure," in the words of the Smithsonian's FAQ page? Are Americans so culturally illiterate that they need to be told that jazz is a national treasure, or are they aware of this and simply apathetic towards jazz? I believe the answer lies in a combination of both factors; it is easy to find someone who has never heard a Charlie Parker recording, but that person would not necessarily be moved by listening to a recording. For many people, jazz does not resonate, especially if the jazz in question was recorded more than half a century ago. Therein lies the challenge of promoting art to the masses: If no one wants to listen to jazz in the first place, telling them that they are missing out on this "treasure" may not make them any more likely to embrace jazz. This does not bode well for Jazz Appreciation Month.

- Plenty of musicians and critics have called out other musicians and critics for fostering a definition of jazz that makes it seem like a dead art, whose greatest practitioners are long-gone and whose momentum has stagnated into a maintenance of tradition, rather than the creation of new art relevant to the current day. By promoting Jazz Appreciation Month under the auspices of the national museum, are the American people reinforcing the idea that jazz is a museum-piece, to be studied as a relic of the past?

- Could the Smithsonian have picked a worse logo for Jazz Appreciation Month than the clip-art-inspired dreck at the top of this entry? Clearly, the Smithsonian needs to hire a new graphic designer.

30 April 2008

Jazz Appreciation Month

Today marks the end of Jazz Appreciation Month. I did not know that Jazz Appreciation Month even existed until my brother mentioned it to me the other day (he himself did not know until it was mentioned on one of the jazz stations on XM Satellite Radio). The fact that Jazz Appreciation Month, brought to you by the Smithsonian, exists brings a few questions to mind:

27 April 2008

Review

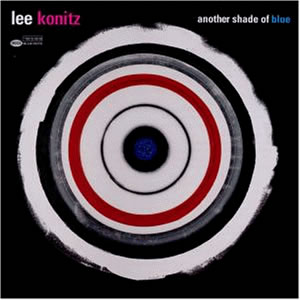

Lee Konitz

Another Shade of Blue

Another Shade of Blue

One of the great pleasures of jazz is the experience of listening to a group of musicians explore a common language in a way which creates something new and unexpected; what Whitney Balliet meant when he wrote of the "sound of surprise." Lee Konitz achieves this evanescent feeling on Another Shade of Blue, his second live disc of a two-night engagement Charlie Haden and Brad Mehldau. On the disc, the three tackle a trio of standards bookended by two originals, one by Konitz and another by the whole group. The live setting allows them to stretch out and explore in a way which keeps them from falling into the inevitable ruts that come with playing these tunes over the course of a career. More impressively, the trio manage to explore the deepest crevasses of these tunes without noodling or losing focus.

In the hands of professionals such as these, the tunes come alive with a sense of exploration. Konitz stretches the blues on the title track to its outer limits, playing around with harmony and phrasing to create an ambiguous feel, neither major nor minor. With Konitz and Haden laying out, Mehldau breaks out of rhythm in "Everything Happens to Me," interposing a strong left hand with sophisticated harmony that has come to be characteristic of his work. Haden anchors the band. His accompaniment on "Another Shade of Blue" is perfectly accented, neither too forceful nor too soft, giving it the feel of a heartbeat. His soloing is quite straightforward and melodic; Haden allows his inherent sense of lyricism to shine through to good effect. The trio pulls off a particularly piquant performance on "Body and Soul," no easy feat.

The absence of a drummer allows the group to play with timing and tempo in the ballads. On the blues which opens the album, the lack of a drummer allows for a subtler swing than one would expect, which was a pleasant surprise. This set may not bring the type of edge-of-your-seat excitement one might expect from such a supergroup, but Konitz, Haden, and Mehldau keep things interesting and provide a fresh, thoughtful, and fun approach to some well-worn tunes - exactly what you would have hoped for had you been at the Jazz Bakery in L.A. when Another Shade of Blue was recorded.

Track Listing: Another Shade of Blue; Everything Happens To Me; What's New?; Body and Soul; All of Us

Personnel: Konitz, alto saxophone; Brad Mehldau, piano; Charlie Haden, bass

25 April 2008

Friday Album Cover: Way Out West

Sonny Rollins

Way Out West

This week's album cover is Sonny Rollins' Way Out West, featuring Sonny as a western gunslinger. Sonny included some western-themed tunes like "I'm an Old Cowhand" and his own original, "Way Out West" on the album. For the cover, photographer William Claxton completed the motif, with Sonny wielding his tenor like a six-shooter, sure of his place as the top tenor saxophonist in jazz when the album was released in 1957.

18 April 2008

Friday Album Cover: Out To Lunch

Eric Dolphy

'Out To Lunch!'

'Out To Lunch!'

I could not think of a better a representation of the avant-garde Eric Dolphy's saxophone style than the clock this album cover. Another gem from Reid Miles and Blue Note, this cover combines the tinted black & white photo so often employed on the label's covers with bold and simple typefaces to give the viewer an idea of the wild music contained on the disc. Nothing much needs to be written about the cover to Out To Lunch; of all the iconic album covers put out by Blue Note, this remains one of the best and most memorable.

I could not think of a better a representation of the avant-garde Eric Dolphy's saxophone style than the clock this album cover. Another gem from Reid Miles and Blue Note, this cover combines the tinted black & white photo so often employed on the label's covers with bold and simple typefaces to give the viewer an idea of the wild music contained on the disc. Nothing much needs to be written about the cover to Out To Lunch; of all the iconic album covers put out by Blue Note, this remains one of the best and most memorable.

17 April 2008

Solo Monk: An Appreciation

Thelonious Monk: "Don't Blame Me"

From Thelonious Monk Live in '66, Jazz Icons Series

From Thelonious Monk Live in '66, Jazz Icons Series

There is perhaps no greater joy to be found in the history of jazz performance than a solo performance of Thelonious Monk. Even when playing one of his most introspective and quiet tunes, like Monk's Mood, for instance, Monk had the ability to surprise the listener in a way that would bring a soft chuckle, even as he was pouring his soul into the piano. This recording of the standard "Don't Blame Me," recorded in 1966 for Danish television and released on the Jazz Icons series a few years ago, is a favorite of mine. I think this performance is representative of the inimitable qualities of a Monk performance which get thrown about whenever his music is discussed: the employment of negative space to give greater meaning to his phrases, spontaneity, complex harmonies, and the stride-piano foundation which is evident in most of his solo playing.

Following a familiarly Monkish cadenza, Monk begins the Fields/McHugh composition with a simply stated melody in the first few bars, but quickly moves into variations on the melody. His improvisation on standards such as this deftly combines melodic variation interposed with complex rhythmic and harmonic figures which keep things interesting while expanding on the song's structure (see for instance the phrase beginning at 0:35). Monk's melodic conception was surpassed by only a very few (only Sonny Rollins comes to mind right now). He interspersed and juxtaposed phrases so well that he could create something new night after night without having to constantly reinvent himself. This recording is a perfect example of this trait; Monk does not pull off any technical feats of strength, or use any phrase of his we've never heard before, but it is the combination and sequence of his phrases that keeps the listener interested.

Monk employs his left hand in a quarter-note rhythm that comes straight out of the school of stride piano from which he drew much of his early inspiration. This is a common theme of solo Monk (for a more forceful example, listen to his shift into a stride rhythm in the solo section of "Monk's Point" in Solo Monk

Besides demonstrating the continuity inherent in jazz, Monk's use of the stride rhthym in the left hand is indicative of what some musicians (including Billy Taylor and Wynton Marsalis, among others) have identified as the democratic aspect of jazz. This is not a new idea, indeed, the U.S. State Department cited the "democratic nature of jazz" when it proposed sponsoring international tours of jazz musicians as a means of promoting goodwill during the Cold War. This democratic theory of jazz states that a jazz ensemble, by promoting free individual expression in the framework of a cooperative group, mimics the ideals of personal liberty and cooperation inherent in the American Constitution. Monk's solo style, at first glance an exercise in total personal freedom, upon further examination fits well into this archetype. Throughout the entire performance, while expounding on fanciful melodies and accentuating ambiguous harmonies, the listener hears the constant (if subtle) beat of the quarter note in the left hand. These quarter notes are not only keeping time but also imposing discipline on Monk's right hand, keeping it within the rhythmic framework of the song and preventing Monk from improvising his way into a black hole of abstraction.

Although this democratic theory of jazz is of limited use, especially when considered outside of its original Cold War framework, it fits well into Monk's style. Though he is perhaps the ultimate individualist of jazz, Monk at the same time created a music that is both accessible and challenging to the scores of musicians that followed him. It is this quality of Monk which keeps his music fresh a half century after its creation, presenting a firm structure while allowing the improviser unlimited freedom. It is why I can never tire of his music.

11 April 2008

Friday Album Cover: A New Perspective

Note: Friday Album Cover will be a weekly feature in which I discuss an iconic, innovative, or otherwise interesting jazz album cover. Though examining album covers is not necessarily imperative to an understanding of jazz, plenty of people, myself included, find them to be a noteworthy facet of a music in which image and mythology often play a central role. Enjoy...

Donald Byrd

A New Perspective

What better way to open this feature than with one of the classic covers of the Blue Note catalogue? Blue Note founders Alfred Lion and Francis Wolff employed the talented graphic designer Reid Miles to design much of the label's distinctive cover art during the 1950s and 1960s, often employing the photographs of Wolff, who always had his camera nearby in the studio. As a result, the album covers of Blue Note's catalogue are among the most memorable and distinctive in the history of jazz.

What better way to open this feature than with one of the classic covers of the Blue Note catalogue? Blue Note founders Alfred Lion and Francis Wolff employed the talented graphic designer Reid Miles to design much of the label's distinctive cover art during the 1950s and 1960s, often employing the photographs of Wolff, who always had his camera nearby in the studio. As a result, the album covers of Blue Note's catalogue are among the most memorable and distinctive in the history of jazz.Recorded in 1963, Donald Byrd's A New Perspective employs an eight-voice choir in addition to his septet to give the music a distinctive gospel tinge. Byrd intended to innovate on this album, using the choir to bring gospel to the fore in an unprecedented manner. Hence, the album's title and unique album cover, in which Byrd is photographed next to a Jaguar roadster at a peculiar angle. The passenger-side headlight dominates the album cover, and serves multiple allusions. Byrd intends to shine new light on the influence of gospel on jazz, and the term "shine a light" is a familiar trope in gospel lyrics. Additionally the odd angle of the photograph (the new perspective) forces the audience to look at Byrd in a new way. All things considered, the album cover is quite memorable and fits in with the concept of the music quite well.

09 April 2008

Martin Luther King on Jazz

I know I'm a little late in this remembrance, but Friday was the fortieth anniversary of the assassination of Dr. Martin Luther King. I thought I would post his speech from the 1964 Berlin Jazz Festival, in which he champions jazz both for leading the African American quest for racial identity and for lending power to the civil rights movement.

God has brought many things out of oppression. He has endowed his creatures with the capacity to create - and from this capacity has flowed the sweet songs of sorrow and joy that have allowed man to cope with his environment and many different situations.Text courtesy of HR-57 Center for the Preservation of Jazz & Blues

Jazz speaks for life. The Blues tell the story of life's difficulties, and if you think for a moment, you will realize that they take the hardest realities of life and put them into music, only to come out with some new hope or sense of triumph. This is triumphant music.

Modern Jazz has continued in this tradition, singing the songs of a more complicated urban existence. When life itself offers no order and meaning, the musician creates an order and meaning from the sounds of the earth which flow through his instrument.

It is no wonder that so much of the search for identity among American Negroes was championed by Jazz musicians. Long before the modern essayists and scholars wrote of "racial identity" as a problem for a multi-racial world, musicians were returning to their roots to affirm that which was stirring within their souls.

Much of the power of our Freedom Movement in the United States has come from this music. It has strengthened us with its sweet rhythms when courage began to fail. It has calmed us with its rich harmonies when spirits were down. And now, Jazz is exported to the world. For in the particular struggle of the Negro in America there is something akin to the universal struggle of modern man. Everybody has the Blues. Everybody longs for meaning. Everybody needs to love and be loved. Everybody needs to clap hands and be happy. Everybody longs for faith. In music, especially this broad category called Jazz, there is a stepping stone towards all of these.

07 April 2008

Review

Miles Davis' "Second Quintet" of the 1960s (featuring Wayne Shorter, Ron Carter, Herbie Hancock, and Tony Williams) does not quite get the attention it deserves at times. It is overshadowed in memory by John Coltrane's and Ornette Coleman's groundbreaking quartets, and is sometimes seen as merely a bridge between Miles' straightforward hard bop of the 1950s and early 1960s and his wild fusion experiments later in the decade. Jeremy Yudkin, a musicologist at Boston University, thinks this band, and especially the album Miles Smiles, deserves a place in the pantheon of Miles alongside his other celebrated works like Kind of Blue and Birth of the Cool. Moreover, Yudkin thinks Miles Smiles is best understood as the album in which Miles solidifies the style of postbop, making it an unrecognized pillar of The Jazz Tradition. In this book, Yudkin both attempts to understand Miles Smiles within the development of Miles Davis' artistic development and to employ Miles Smiles as a codification of postbop, a heretofore "slippery title" which other scholars of jazz have used in a temporal, but not necessarily stylistic sense.

Yudkin is at his best when placing Miles Smiles in the context of the Miles Davis canon. He deftly compares Miles' use of space in Miles Smiles to earlier examples in his career like "Boplicity" from the Birth of the Cool sessions in 1950 and "Bag's Groove" in 1954. He also identifies Miles' use of pyramidic structures and modes as points of continuity between Miles Smiles and Miles' earlier canon. Miles Smiles emerges from this study as a logical continuance from Birth of the Cool, Milestones, and Kind of Blue. Miles Smiles emerges as a work with deep roots in Miles' past, which reveal themselves as the foundation of his style evident throughout his evolution as an artist.

Yudkin falls short, however, in demonstrating how Miles Smiles translates into a specimen of postbop, and not just another link in the Miles Davis chain. Defining postbop as "freedom anchored in form," he concludes that Miles developed "a new approach to music, an approach that was abstract and intense in the extreme, with space created for the rhythmic and coloristic independence of the drummer--an approach that incorporated modal and chordal harmonies, flexible form, structured choruses, melodic variation, and free improvisation." Under this definition; flexible, abstract-yet-melodic, modal and chordal; postbop continues to seem like a catch-all definition, the kind which Yudkin dismisses as "slippery" at the outset of his work. The definition offered by Yudkin seems better utilized as a classification of Miles rather than a definition of postbop.

Indeed, the difficulty with defining postbop as a style underscores the impossibility of classifying jazz at this point in the music's history. After the rise of free jazz and the avant-garde, jazz loses its linear narrative form. Countless styles abound, finding strange connections. Roswell Rudd goes from playing traditional dixieland to free jazz; Stanley Crouch transforms from free jazz drummer into the intellectual godfather of jazz neoclacissism. Yudkin illustrates the complicated nature of classifying a mature and diverse art form like jazz: in which it is easier to position an artist within a web of influences than it is to unite a group of artists under a stylistic banner.

Nevertheless, many will find this book useful. Yudkin includes some very helpful transcriptions from Miles Smiles, and, as anyone who has tried to figure out the chord changes to Nefertiti can attest, deciphering the music of this group is no easy matter. More than that, though, Yudkin has shined a spotlight on a body of work which can never get the amount of attention it really deserves. We owe him thanks for reminding us what pure genius Miles Smiles is, and remains.

06 April 2008

Self Portrait in Three Colors

I.

As this is the inaugural post on the blog, I'll begin with an introduction of sorts. I first listened to jazz in 1996, when I was in seventh grade and joined the Arvida Middle School Jazz Band under the direction of Roger Faulmann. I had been playing trumpet for a year at that point. This band was my first exposure to jazz, though the band did not play much jazz per se (the repertoire was a mostly American popular songs with some oldies and traditional big band charts thrown in for good measure). Besides the borderline-jazz and non-jazz tunes, we played arrangements of Count Basie, Benny Goodman, Glenn Miller, and Duke Ellington. So the first jazz I was listening to came from that source. Soon enough, I was broadening my horizons to Miles, Bird, Monk, Trane, and all the other jazz greats one would expect an adventurous neophyte to discover. This continued into high school, where I blossomed into a full-fledged music nerd, playing in multiple bands at Coral Reef Sr. High in Miami, Florida, and developing into a mildly competent jazz trumpeter.

By college I had given up all aspirations of becoming a musician, but used jazz in a research focus for my history degree, writing an undergraduate thesis on the racial politics of hard bop for the history department at the University of Florida. This interest continued at the University of Virginia, where I wrote another thesis (this time for an M.A.) on the discourse of race in the jazz community of the 1960s. before dropping out of grad school with an M.A., I had ambitions of becoming a historian who examined jazz and American culture. I now work in the "real world" at stock market research firm, and have decided to continue writing about jazz on this blog.

I've always had a passion for jazz; for the way it challenged me, surprised me, made me laugh; for the way musicians incorporated disparate elements into their music while stamping out a unique musical identity. I plan on building a catalog of critical writings, discussing jazz of many eras, reviewing books and new albums that come out, and trying to find an answer to the eternal question, "What is jazz?" I hope you'll at least find my posts thoughtful and occasionally thought-provoking.

II.

Because every once in awhile I am asked by friends for a brief primer into jazz, I often think of what to recommend to the nascent jazz listener. I've come up with what I think is a good list to give someone a basic discography on which to build a collection. While I try to keep it broad, I think the list still reveals what I like the most and what I find to be the most important building blocks of jazz, so I include it below to give you an idea of my own tastes. I should note that most was recorded before 1970. This is not because I think good music ceased to be recorded after this point, it is because I feel one should first be introduced to "The Jazz Tradition" (I will address the problems of such a canonization of a tradition and attempt an explanation of the Jazz Tradition in later posts). This allows the listener a better understanding of the context out of which a jazz musician from any era comes. I also try not to repeat artists, so I can include more.

So, acknowledging those caveats, here is my list, in chronological order:

Of course, when I actually make this recommendation, I often double the list so I can include Sonny Rollins, Charles Mingus, Lee Morgan, more Miles and Monk, Bill Evans, etc. But the exercise is no fun if you do not impose any boundaries...

III.

Since the above list excluded everything after 1965 (I was unable to include any fusion on the list, which is one of the reasons it took me so long to narrow it down), I will include a second list of everything since then for the beginning listener who is familiar with The Jazz Tradition.

That's the introduction. Stay tuned...

As this is the inaugural post on the blog, I'll begin with an introduction of sorts. I first listened to jazz in 1996, when I was in seventh grade and joined the Arvida Middle School Jazz Band under the direction of Roger Faulmann. I had been playing trumpet for a year at that point. This band was my first exposure to jazz, though the band did not play much jazz per se (the repertoire was a mostly American popular songs with some oldies and traditional big band charts thrown in for good measure). Besides the borderline-jazz and non-jazz tunes, we played arrangements of Count Basie, Benny Goodman, Glenn Miller, and Duke Ellington. So the first jazz I was listening to came from that source. Soon enough, I was broadening my horizons to Miles, Bird, Monk, Trane, and all the other jazz greats one would expect an adventurous neophyte to discover. This continued into high school, where I blossomed into a full-fledged music nerd, playing in multiple bands at Coral Reef Sr. High in Miami, Florida, and developing into a mildly competent jazz trumpeter.

By college I had given up all aspirations of becoming a musician, but used jazz in a research focus for my history degree, writing an undergraduate thesis on the racial politics of hard bop for the history department at the University of Florida. This interest continued at the University of Virginia, where I wrote another thesis (this time for an M.A.) on the discourse of race in the jazz community of the 1960s. before dropping out of grad school with an M.A., I had ambitions of becoming a historian who examined jazz and American culture. I now work in the "real world" at stock market research firm, and have decided to continue writing about jazz on this blog.

I've always had a passion for jazz; for the way it challenged me, surprised me, made me laugh; for the way musicians incorporated disparate elements into their music while stamping out a unique musical identity. I plan on building a catalog of critical writings, discussing jazz of many eras, reviewing books and new albums that come out, and trying to find an answer to the eternal question, "What is jazz?" I hope you'll at least find my posts thoughtful and occasionally thought-provoking.

II.

Because every once in awhile I am asked by friends for a brief primer into jazz, I often think of what to recommend to the nascent jazz listener. I've come up with what I think is a good list to give someone a basic discography on which to build a collection. While I try to keep it broad, I think the list still reveals what I like the most and what I find to be the most important building blocks of jazz, so I include it below to give you an idea of my own tastes. I should note that most was recorded before 1970. This is not because I think good music ceased to be recorded after this point, it is because I feel one should first be introduced to "The Jazz Tradition" (I will address the problems of such a canonization of a tradition and attempt an explanation of the Jazz Tradition in later posts). This allows the listener a better understanding of the context out of which a jazz musician from any era comes. I also try not to repeat artists, so I can include more.

So, acknowledging those caveats, here is my list, in chronological order:

- Hot Five and Hot Seven Recordings, Louis Armstrong

- Decca Recordings, Count Basie

- The Blanton-Webster Band, Duke Ellington

- Yardbird Suite (or any other collection with the mid-'40s sides with Dizzy Gillespie), Charlie Parker

- Moanin', Art Blakey and the Jazz Messengers

- Kind of Blue, Miles Davis

- The Shape of Jazz to Come, Ornette Coleman

- Monk's Dream, Thelonious Monk

- A Love Supreme, John Coltrane

- Maiden Voyage, Herbie Hancock

Of course, when I actually make this recommendation, I often double the list so I can include Sonny Rollins, Charles Mingus, Lee Morgan, more Miles and Monk, Bill Evans, etc. But the exercise is no fun if you do not impose any boundaries...

III.

Since the above list excluded everything after 1965 (I was unable to include any fusion on the list, which is one of the reasons it took me so long to narrow it down), I will include a second list of everything since then for the beginning listener who is familiar with The Jazz Tradition.

- Bright Size Life, Pat Metheny

- Standard Time, Vol. 1, Wynton Marsalis

- Soul on Soul, Dave Douglas

- Tonic, Medeski, Martin & Wood

- Whisper Not, Keith Jarrett

- Bill Frisell with Dave Holland and Elvin Jones, Bill Frisell, Dave Holland, and Elvin Jones

- Prime Directive, Dave Holland Quintet

- Oh!, ScoLoHoFo

- Modernistic, Jason Moran

- House on Hill, Brad Mehldau

That's the introduction. Stay tuned...

02 April 2008

What is The Jazz Tradition?

I make references to The Jazz Tradition frequently, so here is a handy definition for you.

The Jazz Tradition is a reduction of a basic jazz canon which most musicians, critics, and listeners can agree upon. The Jazz Tradition is by nature restrictive and exclusive, since most jazz enthusiasts have a hard time agreeing on who should and should not be included in the pantheon of essential jazz musicians, beyond the obvious examples like Thelonious Monk or Coleman Hawkins. The Jazz Tradition is always capitalized. The Jazz Tradition is both useful and limiting, as it creates a reference point for what has historically come to be known as jazz but belies the complexity, depth, and breadth of the music.

The Jazz Tradition is an anachronistic term used in a historical sense to describe the landmarks of jazz that shaped the music until the present day. If a musician is a significant stylistic and cultural influence in jazz history, then he or she is part of The Jazz Tradition. Charlie Parker and Clifford Brown are part of The Jazz Tradition, but Muhal Richard Abrams and John McLaughlin are not part of The Jazz Tradition. All four play jazz, but only the first two fit within the confines of The Jazz Tradition.

Mythology plays an important role in The Jazz Tradition. The Jazz Tradition features many types of martyrs; the saintly Clifford Brown, the tragic Charlie Parker, the enlightened John Coltrane. Then there are the creation myths: Louis Armstrong's rites of passage in Storyville, jam sessions at Minton's, Ornette Coleman's debut at The Five Spot. The Jazz Tradition is not merely a canon, but a historical narrative with characters and scenes as colorful as those found in a Steinbeck novel.

But The Jazz Tradition is also an ephemeral idea, so don't spend too much time trying to define it; you will only end up going in circles.

The Jazz Tradition is a reduction of a basic jazz canon which most musicians, critics, and listeners can agree upon. The Jazz Tradition is by nature restrictive and exclusive, since most jazz enthusiasts have a hard time agreeing on who should and should not be included in the pantheon of essential jazz musicians, beyond the obvious examples like Thelonious Monk or Coleman Hawkins. The Jazz Tradition is always capitalized. The Jazz Tradition is both useful and limiting, as it creates a reference point for what has historically come to be known as jazz but belies the complexity, depth, and breadth of the music.

The Jazz Tradition is an anachronistic term used in a historical sense to describe the landmarks of jazz that shaped the music until the present day. If a musician is a significant stylistic and cultural influence in jazz history, then he or she is part of The Jazz Tradition. Charlie Parker and Clifford Brown are part of The Jazz Tradition, but Muhal Richard Abrams and John McLaughlin are not part of The Jazz Tradition. All four play jazz, but only the first two fit within the confines of The Jazz Tradition.

Mythology plays an important role in The Jazz Tradition. The Jazz Tradition features many types of martyrs; the saintly Clifford Brown, the tragic Charlie Parker, the enlightened John Coltrane. Then there are the creation myths: Louis Armstrong's rites of passage in Storyville, jam sessions at Minton's, Ornette Coleman's debut at The Five Spot. The Jazz Tradition is not merely a canon, but a historical narrative with characters and scenes as colorful as those found in a Steinbeck novel.

But The Jazz Tradition is also an ephemeral idea, so don't spend too much time trying to define it; you will only end up going in circles.

01 April 2008

Table of Contents

Longer-Form Musical Analysis

Some recent reviews:

Remembrances

- Hard Bop

- On Medeski Martin & Wood

- Solo Monk: An Appreciation

- Time Out Revisited

- Christian Scott and a New Jazz Orthodoxy

- Barack Obama: Jazz President?

- Jazz Appreciation Month

- Jazz Wars Posts

- Martin Luther King on Jazz

- Media Criticism

- On Booker Little and Jazz Mythology

- On the Jazz Press and Media Criticism

- An Unoriginal Lament Concerning Technology

- Will Someone Get the Led Out?

- Wynton Marsalis and Ronald Reagan

Some recent reviews:

- Mary Halvorson Quintet: Saturn Sings

- Vijay Iyer: Solo

- Avishai Cohen: Introducing Triveni

- The Bad Plus: Never Stop

- Jason Moran: TEN

- The Birth of Bebop and Hotter Than That

- Robin DG Kelley: Thelonious Monk: The Life and Times of an American Original

- Ben Ratliff: The Jazz Ear: Conversations over Music

- Gabriel Solis: Monk's Music

- Jeremy Yudkin: Miles Smiles

- Icons Among Us: Jazz in the Present Tense

- Jazz Profiles With Nancy Wilson

- The Jazz Session Podcast

- Miles Electric: A Different Kind of Blue

- Take Five: A Weekly Jazz Sampler

- 8 Essential Trumpet Solos

- Best Working Groups in Jazz (2008)

- Indispensable Jazz Blogs

- Jazz Now

- New Standards

- Starting a Jazz Library

- Under-the-Radar Live Albums

Remembrances

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)